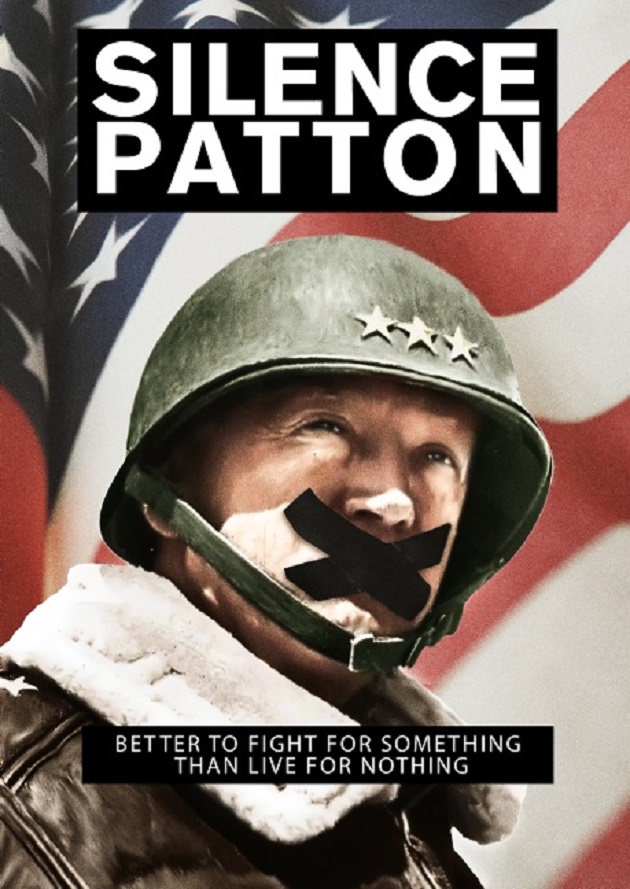

A new graphic-novel-style documentary film, Silence Patton: First Victim of the Cold War (released earlier this month) takes a deep look at the career, character and demise of General George S. Patton, the iconic and controversial four-star general from World War II. The 90-minute, graphic-novel-style documentary presents a depth of research based on the general’s own diaries and focuses on little known post-war geopolitics and carnage that laid the groundwork for the Cold War.

As the collective memory of World War II recedes, it is easily forgotten that war is ugly; to win a war, it takes flawed, impolite, ugly types like Patton, who are good at waging war. More than seven decades later, many Americans choose not to acknowledge that Patton, with all of his rough edges, was one of us. And Patton’s traits — the ones not shared at polite dinner parties — were the very traits needed to survive during the extreme moments of war.

Between 1941 and 1945, world leaders were larger than life: Churchill, Stalin, Roosevelt, Truman. Yet none were more outsized and confounding than George S. Patton. Nearly three-quarters of a century later, questions about him linger. Was Patton crass or merely tactless? Was he impulsive or strategic? Good or evil? Admirable or despicable? Bombastic? Revered? Reviled? He was all these and more. Silence Patton explores the enigma of the man who was perhaps the “winningest” general in modern history, and yet was abruptly relieved of his command.

General Patton was also a student of war and military life. He had a massive library, which he donated to West Point. Every book is heavily annotated with comments he scribbled in the margins. Patton was an ornery and profane character but also had a humorous side, a twinkle in his eye.

Patton did everything in his power to compensate for his high-pitched voice, which was described by General Omar Bradley as “almost comically squeaky and high pitched, altogether lacking in command authority.” The nickname for him was Mickey Mouse. In his memoirs, Bradley wondered if Patton’s “macho profanity was an unconscious overcompensation for his most serious personal flaw.” George C. Scott’s portrayal of Patton in the 1970 Academy Award winner of the same name captured the irascible general’s bold spirit; it did not accurately capture the general’s distinctively shrill voice.

Patton’s all-out warrior mentality is reflected in his memoirs, which are filled with ethnic slurs and what would strike even modern ears as “colorful” language. General Bradley, at first his junior and later his senior officer, claimed Patton had an incomparable fierceness. In his book, A Soldier’s Life, Bradley described Patton this way: “He seemed to be motivated by some deep, inexplicable martial spirit. He dressed as if he had just stepped out of a custom military tailor shop and has his own private bootblack. He was unmercifully hard on his men…Most of them respected but despised him.”

Patton was proud of his ferocity and his fiery rhetoric. Lindsey Nelson, who served under Patton and later became well known as a New York Mets broadcaster, tells us the general spoke in extremes in that famously squeaky voice: “We’ll rape their women and pillage their towns and run the pusillanimous S.O.B.s into the seas.”

According to Patton biographer Stanley Hirshon, it was his unbridled language that later led to the massacre of Italian soldiers in Sicily. He wanted the 45th division to be remembered as “The Killer Division.”

Yet, Patton emerges from the war as the superior general. Averill Harriman, then American ambassador to Russia, claimed that Stalin told him: “No general in the Russian Army can do what Patton did.” Stalin placed Patton on a pedestal, but the feeling was anything but mutual. Patton despised Stalin and the Red Army.

At the conclusion of the war, Patton attempted to keep certain Nazi divisions intact in anticipation of what he felt was an inevitable war with Moscow. Instead, Patton’s warnings about Russian intentions were ignored. Even with a plausible chance to save Prague from Stalin’s armies, the point of Patton’s spear was blunted.

This was the same Patton whom Eisenhower earlier had called to headquarters in Verdun to orchestrate a plan to beat back the Germans. In December 1944, Allied forces were near defeat in what became known as the Battle of the Bulge. If the Nazis captured Bastogne, the rout would be complete and the war would continue. Yet within a week, through boldness and ingenuity, Patton and his Third Army relieved the 101st Airborne Division from the Germans.

It was also the same Patton who argued with and often ignored his commanders, taking as many liberties as possible. Despite orders, for example, he did not slow down when he was at the point of advancement into Berlin in 1945 but instead moved to cut off the Russians before they could take the city. He famously declared: “Some goddamn fool once said ‘flanks have to be guarded.’ Before he figures out where my flanks are I’ll be cutting the bastard’s throat.”

The incident was an international flashpoint. Patton was fired. His intelligence and sanity were questioned and his phone was bugged. He no longer had an army to command, and this fiercest of generals was given a desk job documenting the war.

The question at the heart of Silence Patton remains: Did Patton know something others did not? He maintained that Berlin could be taken, as well as Prague — an argument subsequently made by many historians. Not saving the people of Eastern Europe, contended Patton, amounted to breaking a promise and would result in an unfinished war. He was insightful in predicting the Cold War. Only a few years after Patton’s prescient warning, Germany would need its disbanded army back to stop Russian aggression in post-war Berlin.

Image courtesy of Robert Orlando

After his “reassignment,” Patton continued to mouth off publicly against his superiors and against the Russians. He threatened to share all he had observed during the war once he returned to the U.S., promising to “take the gag off.” He wrote a tell-all memoir that, even though softened by his family, revealed a not-so-silent Patton. The memoir allowed him to speak for himself in all his rawness and honesty. A voice that would roar!

On his last day in the European theater before leaving for home, Patton was injured in a car accident. He later died in a German hospital. His death has been cloaked in suspicion and mystery, in part because of the sloppy investigation that followed and because he had a long list of enemies, foreign and domestic. Many observers have come to believe that Patton’s enemies did what they had always intended to do: Silence Patton.

The Unified-Sony Pictures released Silence Patton film unleashes Patton’s voice, in all its political incorrectness, and finally removes the gag, as if it were a historical confession for a modern audience to hear and decide for themselves.

Robert Orlando is a filmmaker. You can visit the www.silencepatton.com website for additional details about production and screenings.

The views and opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of The Daily Caller.