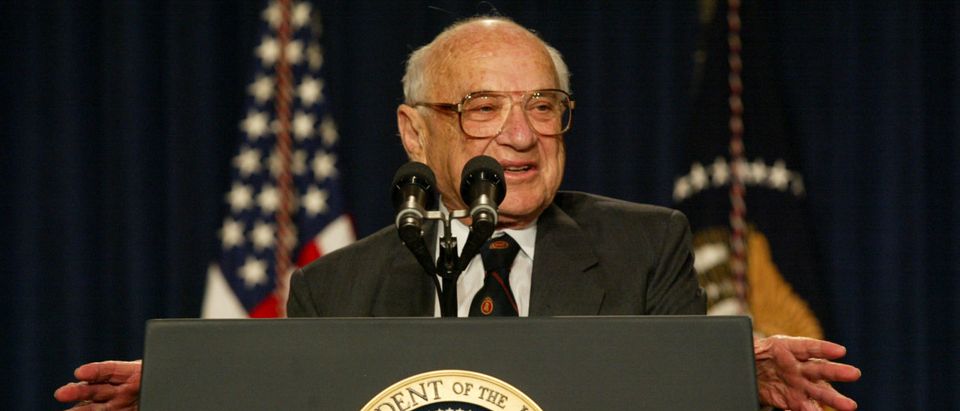

Milton Friedman emailed me. Yes, one of the most distinguished economists of the 20th century took the time to send me a personal note. I received that note nearly twenty years ago. His message was profound, and it resonates to this very day.

In late 2002, I was transferred from the Bush White House to the Treasury’s Office of Economic Policy as a deputy assistant secretary.

Those were trying times. The U.S. had recently engaged in a war in Afghanistan. We were also on the verge of a second war with Iraq.

Due to those conflicts, and an unexpected recession, the federal budget quickly slipped from surplus into deficit.

More than a few Washingtonians — that’s contemporary Washington-speak for “swamp-dwellers” — called for a return to “fiscal discipline.” Yet, in a town whose occupants are at times baffled by the definition of “is,” (recall Bill Clinton’s August 1998 deposition) fiscal discipline is an exceptionally elusive concept. How can voters distinguish the doers from the talkers?

The talkers believe fiscal discipline is a courageous politician’s unrepentant willingness to raise taxes. (Hello, Bernie Sanders!) In truth, raising taxes is the antithesis of fiscal discipline. Raising taxes is akin to buying larger pants in lieu of exercise and a low-calorie diet. True fiscal discipline entails keeping government spending under control to minimize the drain of resources from the private sector to the government.

On December 9, 2002, from my perch at Treasury, I wrote: “Limited federal spending is the only true measure of fiscal discipline. …. A tax increase — regarded by many as the ultimate act of fiscal discipline — merely substitutes one method of extracting resources from the private sector for another.”

In response, Milton Friedman wrote praising my “excellent piece.” (High praise, indeed!)

How the government finances its spending is important. But it’s not nearly as important as the decision to spend in the first place.

Friedman’s praise of my Treasury publication is just as relevant today as it was nearly twenty years ago. Perhaps even more so!

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the federal deficit is expected to surpass $1 trillion this year and every year for the foreseeable future. It’s expected to grow from $1.015 trillion in fiscal year 2020 to $1.742 trillion by 2030. That’s a 71.6 percent increase!

Why is that? Are Republicans cutting taxes to the bone? No. Revenues are expected to grow from $3.6 trillion in 2020 to $5.7 trillion by 2030. That’s an average annual growth rate of 4.7 percent.

It’s just that federal outlays, under current law, are projected to grow from $4.6 trillion in 2020 to $7.5 trillion in 2030 — an annual growth rate of 4.9 percent.

In a $22 trillion economy, even a small growth rate differential can make a HUGE difference.

Slowing the average annual growth rate of federal spending from 4.9 percent to 2.1 percent would balance the budget in 2030 and reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio from 80.8 percent this year to 70.1 percent by 2030, the lowest level since 2012. (That’s not AT ALL likely to happen.)

Fortunately, keeping the federal budget on a sustainable path doesn’t necessitate balancing the budget. Stabilizing and, ideally, gradually reducing the debt-to-GDP ratio, should be our goal. All we need to do is, over time, grow the economy faster than the publicly-held federal debt.

Simple, yes. Easy, no.

Slowing federal spending growth to 3.2 percent would, after a small boost to the debt-to-GDP ratio over the first five years, return the ratio to its current level by 2030 before sending it ever lower in the following years.

Is slowing annual federal spending growth to 3.2 percent for a decade realistic? Defense and non-defense discretionary outlays — currently about 30 percent of federal spending — are projected to grow at an average annual growth rate of 2.4 percent. That’s well below 3.2 percent.

Over the past twenty years, however, I’ve criticized the “false prophets of fiscal discipline” in Congress who seem obsessed with slashing discretionary spending. These false prophets do what they can to cut and restrain discretionary spending while virtually ignoring the true driver underlying federal spending growth: mandatory spending.

Mandatory outlays (aka entitlement spending) currently constitute about 62 percent of federal spending, but they are expected to grow at an average annual rate of 5.5 percent. That rate grows mandatory spending to 65 percent of federal spending by 2030.

Even worse, interest outlays — about 8 percent of federal spending today — are slated to grow 7.9 percent per year over the coming decade, growing interest costs to 11 percent of total federal spending by 2030.

Slowing the growth rate of mandatory spending would also, fortunately, slow the growth of federal interest costs, producing additional savings for every dollar of spending restraint. That’s huge.

The Trump administration knows this well. The president’s fiscal year 2021 budget, released earlier this month, would limit federal spending growth to an average of 3.3 percent per year between now and 2030. The president’s budget does exactly what needs to be done to put federal spending back on a sustainable path. And it’s about time!

Under President Trump’s budget proposal, the debt-to-GDP ratio would rise ever so slightly, but then head lower. Far from unrealistic, it represents a serious and reasonable attempt to put the federal budget back on a sustainable path. A divided Congress may not be willing to accept President Trump’s proposals, but the administration’s math works!

Milton Friedman wrote me nearly twenty years ago in defense of limited government and restrained government spending. The 116th Congress should heed his words.

James Carter served as the head of tax policy implementation on President Trump’s transition team. Previously, he was a deputy assistant secretary of the Treasury and deputy undersecretary of labor under President George W. Bush.